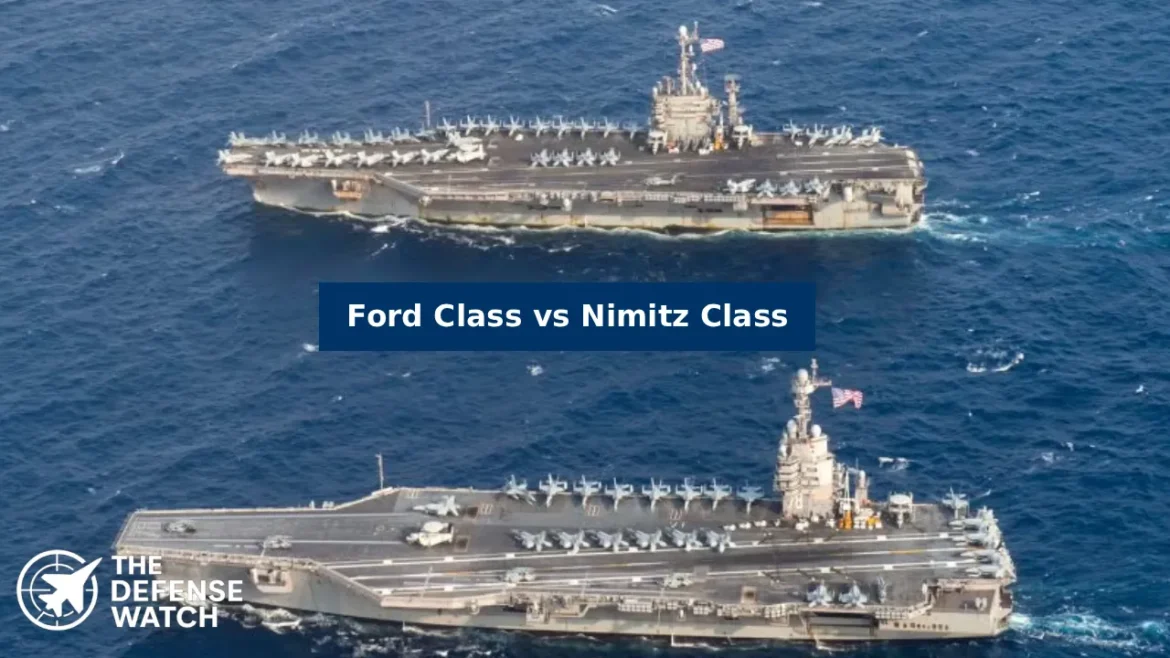

U.S. Navy’s Carrier Evolution: Ford Class vs Nimitz Class

The U.S. Navy plans to eventually acquire ten Ford-class carriers to replace current carriers on a one-for-one basis, starting with USS Gerald R. Ford replacing USS Enterprise, and later replacing the Nimitz-class carriers. This transition represents the most significant technological leap in American carrier design since the Nimitz class entered service in 1975.

Understanding the differences between Ford class vs Nimitz class carriers is essential for assessing the future direction of U.S. naval power projection. While both classes displace approximately 100,000 tons and serve as the centerpiece of carrier strike groups, the Ford class incorporates revolutionary technologies designed to enhance operational efficiency, reduce lifecycle costs, and accommodate future weapons systems.

Launch and Recovery Systems: Steam vs Electromagnetic

The most visible operational difference between the two carrier classes involves how they launch and recover aircraft.

The Nimitz uses a steam-powered catapult system, while the Ford features the more efficient Electromagnetic Aircraft Launch System (EMALS). Traditional steam catapults have served reliably for decades, generating and harnessing steam to slingshot aircraft forward. However, this system requires extensive infrastructure to generate and store steam throughout the ship.

The EMALS accelerates aircraft more smoothly, putting less stress on their airframes. The EMALS also weighs less, is expected to cost less and require less maintenance, and can launch both heavier and lighter aircraft than a steam piston-driven system. This flexibility proves crucial as the Navy integrates new aircraft types, including heavier strike fighters and lighter unmanned aerial vehicles, into carrier air wings.

For aircraft recovery, the Nimitz employs the MK 7 Aircraft Recovery System, whereas the Ford uses the Advanced Arresting Gear system, designed to handle a wider range of aircraft with less maintenance. The AAG system uses advanced control algorithms and energy-absorbing water turbines to safely arrest aircraft while reducing maintenance requirements compared to the hydropneumatic MK 7 system.

Power Generation: Meeting Future Energy Demands

Nuclear propulsion distinguishes both carrier classes from conventional vessels, but their reactor designs differ substantially.

The new Bechtel A1B reactor for the Gerald R. Ford class is smaller and simpler, requires fewer crew, and yet is far more powerful than the Nimitz-class A4W reactor. Two reactors will be installed on each Gerald R. Ford-class carrier, providing a power generation capacity at least 25% greater than the 550 MW of the two A4W reactors in a Nimitz-class carrier.

Even more significant, the Navy outlined a requirement for a minimum increase of 150% in the power-generation capacity for the CVN 21 carrier compared with the Nimitz-class carriers. This dramatic increase in electrical generation capacity addresses limitations that constrained the Nimitz class. As new technologies were added over decades, the Nimitz design’s electrical capacity became increasingly strained, leaving little margin for emerging systems.

The Ford class dedicates only half its electrical generation capacity to currently installed systems, reserving substantial capacity for future directed-energy weapons, advanced sensors, and other power-intensive technologies that may emerge during the carrier’s 50-year service life.

Manning and Automation: Doing More With Less

Personnel costs represent a significant portion of carrier operating expenses, making crew size reduction a key design objective for the Ford class.

Whereas the Nimitz-class carrier has around 6,000 people serving onboard, the Ford class has just over 4,000. Automation makes this possible, reducing the risk to human life in combat situations. More specifically, the Ford-class is larger than its predecessor, the Nimitz-class, but accommodates between 500 and 900 fewer crew members.

This reduction stems from extensive automation throughout the ship. Systems that reduce crew workload have allowed the ship’s company on Gerald R. Ford-class carriers to total only 2,600 sailors, about 700 fewer than a Nimitz-class carrier. The embarked air wing also operates with fewer personnel due to improved aircraft maintenance systems and more efficient ordnance handling.

The automation extends to weapons movement, which previously required extensive manual labor. The movement of weapons from storage and assembly to the aircraft on the flight deck has also been streamlined and accelerated. Ordnance will be lifted to the centralized rearming location via higher-capacity weapons elevators that use linear motors.These electromagnetic elevators can move ordnance without crossing aircraft movement areas, reducing traffic congestion and accelerating rearming operations.

Sortie Generation Rate: Operational Tempo

An aircraft carrier’s value depends on its ability to generate sustained air operations. The Ford class was specifically designed to increase sortie rates compared to its predecessor.

The ship’s systems and configuration are optimized to maximize the sortie generation rate of attached strike aircraft, resulting in a 33 percent increase in SGR over the Nimitz class. While the Nimitz class can sustain 120 sorties per day with surge capability to 240, the Ford-class carriers are intended to sustain 160 sorties per day for 30-plus days, with a surge capability of 270 sorties per day.

This enhanced operational tempo results from multiple design improvements working in concert: the faster EMALS launch system, improved weapons elevators, better flight deck layout with a repositioned island, and more efficient aircraft maintenance procedures.

Physical Configuration and Design

While both classes share similar overall dimensions, the Ford class incorporates significant structural changes.

On the Ford class, the island’s footprint was substantially shrunk and it was moved back by 140 feet on the ship to provide for more deck space overall and to create a deck layout that is supposed to enhance operational tempo substantially The War Zone. The smaller, relocated island creates additional space for aircraft operations and simplifies flight deck traffic flow.

The Ford class has just three aircraft elevators instead of four, but their placement and larger size are supposed to actually enhance operations, not hinder them. By eliminating one elevator and repositioning the remaining three, designers created a more efficient layout that reduces conflicts between aircraft movements on the flight deck.

The island itself reflects technological evolution. Its island, shorter in length and 20 feet taller than that of the Nimitz class, is set 140 feet farther aft and 3 feet closer to the edge of the ship. This unique shape accommodates advanced radar arrays, with the lead ship USS Gerald R. Ford equipped with the Dual Band Radar system featuring six separate AESA arrays providing 360-degree coverage.

Cost Analysis: Initial Investment vs Lifecycle Expenses

The Ford class carries a substantially higher initial procurement cost than the Nimitz class.

The USS Gerald R. Ford is the most expensive warship ever built, with a price tag of $13.3 billion. This compares to the Nimitz-class unit cost of about $8.5 billion in FY 2012 dollars, equal to $11.4 billion in 2024 dollars for newer ships in the class.

However, Navy officials project significant lifecycle cost savings. Each ship in the new class will save more than $4 billion in total ownership costs during its 50-year service life, compared to the Nimitz-class. More recent analysis suggests even greater savings, with the Ford class now slated to cost about $5 billion per ship less than its predecessor, the Nimitz class, over the life of each ship.

These savings derive primarily from reduced crew size and lower maintenance requirements. U.S. aircraft carriers cost over a billion dollars a year to maintain, not including the cost of operating the embarked air wing. The Ford class’s automation and improved systems design should reduce these annual expenses substantially.

Maintenance cycles also differ between classes. The Nimitz class requires five major docked maintenance availabilities during its service life, while the Ford class was designed to require only three such availabilities, further reducing downtime and costs.

Radar and Sensor Systems

Both classes employ advanced radar systems, though specific configurations differ.

The Nimitz class uses a combination of rotating 2D and 3D radar systems, including the SPS-48E 3D air search radar and SPS-49 2D radar. These proven systems provide effective air search and tracking capabilities but require significant space and maintenance.

The lead Ford-class ship introduced the Dual Band Radar combining X-band multifunction radar and S-band volume search radar in a single integrated system with six planar AESA arrays. However, developmental challenges led the Navy to modify its approach for subsequent ships. Starting with USS John F. Kennedy (CVN-79), the Navy will install the Enterprise Air Surveillance Radar (EASR), which uses three arrays and offers greater commonality with other surface combatants.

Defensive Armament

Both carrier classes rely on similar defensive weapons systems, as their primary defense comes from escort vessels in the carrier strike group.

Short-range defensive systems include the Rolling Airframe Missile (RAM) system and Evolved Sea Sparrow Missile (ESSM) for engaging incoming anti-ship missiles. The Close-In Weapon System (CIWS), featuring the Phalanx 20mm gatling gun, provides last-ditch defense against missiles that penetrate outer defensive layers.

The Ford class features updated versions of these systems integrated with more advanced fire control and the Ship Self-Defense System for coordinated defensive responses. However, the basic defensive philosophy remains unchanged—carriers depend heavily on escort vessels equipped with long-range air defense systems like the Aegis Combat System to provide the primary defensive umbrella.

Operational Service and Fleet Status

The Nimitz-class has participated in many conflicts and operations across the world, including Operation Eagle Claw in Iran, the Gulf War, and more recently in Iraq and Afghanistan. With ten ships in service spanning construction from 1968 to 2009, the class represents decades of operational experience and continuous incremental improvements.

The Ford class remains in its early operational phase. USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78) commissioned in July 2017 and completed its first deployment in 2023-2024, including operations in the Eastern Mediterranean during the Israel-Hamas conflict. During the 239 days underway, the carrier logged more than 17,826 flight hours and 10,396 sorties, sailed more than 83,476 nautical miles, and safely transferred 20.7 million gallons of fuel with zero mishaps.

USS John F. Kennedy (CVN-79) is more than 90% complete and expected to deliver in 2025. USS Enterprise (CVN-80) is approximately 35% complete, while USS Doris Miller (CVN-81) is in early construction stages. The Navy is planning to procure CVN-82 and CVN-83 in a two-ship contract later this decade.

Analysis: Evolutionary vs Revolutionary Change

The transition from Nimitz to Ford class represents evolutionary refinement rather than revolutionary redesign in basic carrier operations, but introduces revolutionary changes in specific technological systems.

The fundamental carrier mission remains unchanged—projecting naval aviation power globally through a nuclear-powered mobile airfield. Both classes share similar displacement, speed, and overall operational concepts. The Ford class retains the proven CATOBAR (Catapult Assisted Take-Off But Arrested Recovery) arrangement that distinguishes U.S. supercarriers from smaller STOVL carriers operated by other nations.

However, the accumulation of technological improvements creates qualitatively different capabilities. The combination of EMALS, advanced arresting gear, electromagnetic weapons elevators, tripled electrical generation capacity, and 25% increased sortie generation rate fundamentally enhances operational effectiveness. These improvements should prove increasingly valuable as the Navy integrates new aircraft types, particularly unmanned systems and potentially sixth-generation manned fighters, into carrier air wings over coming decades.

The crew reduction represents perhaps the most significant long-term advantage. With personnel costs comprising a major portion of operating expenses, reducing crew size by 500-900 personnel generates substantial savings. This reduction also makes the ships less labor-intensive to operate during an era when recruiting and retention challenges affect all military services.

Critics note that the Ford class remains vulnerable to the same anti-access/area-denial threats confronting all large surface combatants—anti-ship ballistic missiles, advanced submarines, and saturation attacks by cruise missiles or unmanned systems. However, proponents argue that properly defended carrier strike groups remain highly survivable and uniquely capable of sustained, high-tempo combat operations that no alternative platform can match.

The substantial initial cost difference—approximately $2 billion more than late Nimitz-class ships—raises questions about affordability, particularly given Navy budget constraints and competing priorities. However, if projected lifecycle savings materialize, the Ford class should prove more cost-effective over its 50-year service life despite higher procurement costs.

Ultimately, the Ford class represents the Navy’s commitment to maintaining carrier-centric naval power projection well into the 21st century, incorporating technologies to enhance effectiveness while reducing operating costs. Whether this strategy proves correct depends on how naval warfare evolves over coming decades and whether alternative platforms like submarines, unmanned systems, or distributed surface combatants can replicate carriers’ unique combination of striking power, persistence, and diplomatic presence.

FAQs: Ford Class vs Nimitz Class Carriers

What is the main technological difference between Ford class and Nimitz class carriers?The primary difference involves launch and recovery systems. Ford-class carriers use electromagnetic catapults (EMALS) instead of steam catapults, and Advanced Arresting Gear instead of the hydraulic MK 7 system. These electromagnetic systems reduce stress on aircraft, require less maintenance, and can handle a wider range of aircraft weights.

How many fewer crew members does the Ford class require compared to Nimitz class?Ford-class carriers operate with 500 to 900 fewer personnel than Nimitz-class ships. Where Nimitz-class carriers have approximately 6,000 crew members (including ship’s company and air wing), Ford-class carriers operate with approximately 4,500 personnel due to extensive automation.

Are Ford class carriers more expensive than Nimitz class carriers?Initially, yes—USS Gerald R. Ford cost $13.3 billion compared to approximately $11.4 billion for recent Nimitz-class ships. However, each Ford-class carrier is projected to save $4-5 billion in lifecycle costs over its 50-year service life through reduced crew size and lower maintenance requirements.

Can Ford class carriers launch more aircraft sorties than Nimitz class?Yes. Ford-class carriers can sustain 160 sorties per day with surge capability to 270 sorties, representing approximately a 33% increase compared to Nimitz-class carriers, which sustain 120 sorties daily with surge capability to 240 sorties.

How much more electrical power does the Ford class generate?Ford-class carriers generate at least 25% more total power than Nimitz-class ships, with approximately 150% more power dedicated to electrical generation. This increased capacity supports current systems while reserving substantial power for future directed-energy weapons and advanced sensors.

Get real time update about this post category directly on your device, subscribe now.

1 comment

[…] (leading-edge vortex controllers), and an arrester hook — adaptations that allow deck-based carrier launches and […]