India’s defense manufacturing ecosystem is accelerating efforts to create an independent 110kN aero engine, with multiple private-sector companies seeking Ministry of Defence (MoD) support to develop a high-thrust propulsion solution outside the existing Gas Turbine Research Establishment (GTRE)–Safran joint venture. The emerging initiative, discussions for which advanced in recent months across New Delhi and Bengaluru, signals a growing push toward long-term propulsion self-reliance for India’s fighter aircraft programs.

Background: A Strategic Need for High-Thrust Propulsion

India’s pursuit of a domestic high-thrust turbofan stems from operational and industrial demands tied to the Tejas Light Combat Aircraft (LCA) program, future Advanced Medium Combat Aircraft (AMCA), and increasing emphasis on export competitiveness. While GTRE’s Kaveri derivative programs have delivered limited progress and the GTRE–Safran partnership is working toward a 110kN class engine with blade technology transfer by 2027, private firms believe parallel development is essential to reduce dependency and diversify design risk.

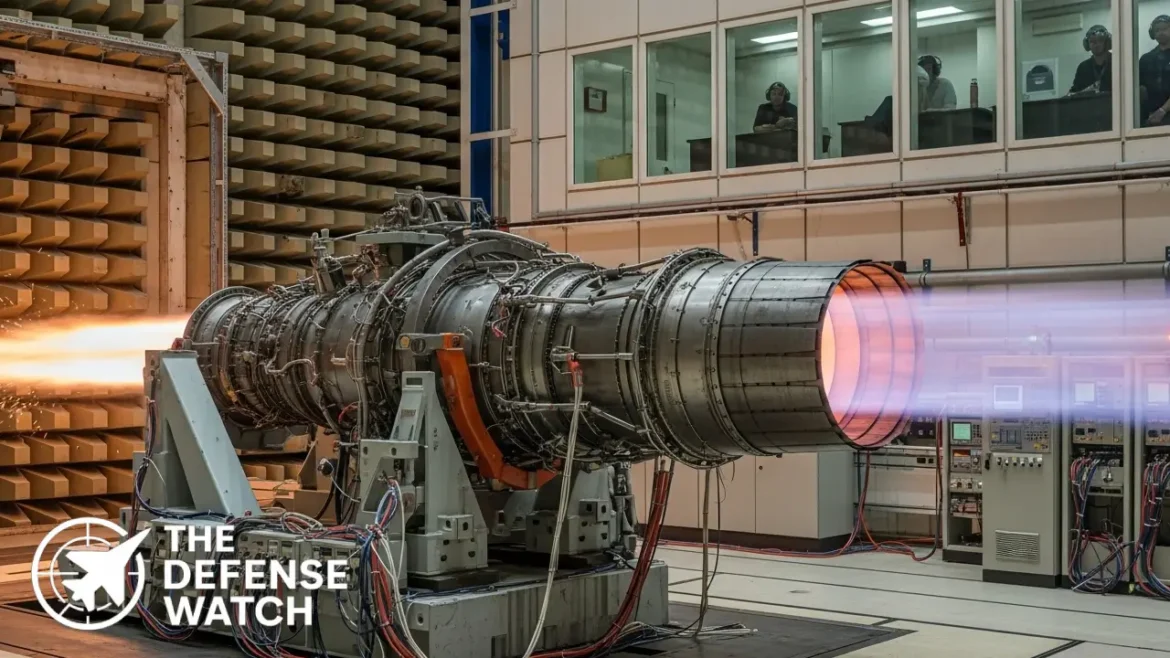

The term 110kN aero engine increasingly serves as a benchmark requirement, capable of powering medium-weight fighters in the 5th-generation class with improved thrust-to-weight ratios, supercruise potential, and higher thermal tolerance.

Private Sector Push: An Independent Pathway

According to industry sources, several leading Indian private aerospace manufacturers have approached the MoD requesting formal endorsement, seed funding, and access to defense testing infrastructure to pursue a clean-sheet 110kN turbofan design. Their proposals reportedly emphasize modular architecture, digital twin development, and high-temperature materials aimed at reducing life-cycle costs and improving growth potential.

Executives familiar with the discussions said companies aim to avoid duplicating GTRE’s ongoing work and instead propose a separate domestic track with global consultancy partnerships.

A senior industry representative noted that the private sector “is ready to assume a significant portion of risk and investment, provided there is clarity on long-term procurement needs and MoD’s willingness to certify and onboard indigenous propulsion systems.”

HAL’s Scaling Plans Add Momentum

State-run Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL), which is scaling Tejas Mk1A production and preparing for prototypes of Tejas Mk2, has been supportive of any propulsion program that creates domestic redundancy. The demand for engines is expected to grow sharply as HAL expands fighter production capacity to meet domestic and export orders.

The parallel Safran technology transfer program—focused on high-pressure turbine blade manufacturing—remains critical for India’s ability to indigenously sustain a 110kN aero engine by 2027. But industry strategists argue that an additional private-sector program could accelerate learning curves and reduce long-term reliance on foreign OEMs.

Government Considerations and Policy Climate

The MoD has previously signaled readiness to support private-sector engine programs via the Technology Development Fund and the Innovations for Defence Excellence (iDEX) scheme, though no large-scale propulsion project has yet been awarded. Officials say a decision on the new proposals may align with the next iteration of India’s defense indigenization roadmap.

Under the current policy, major engine development projects are categorized as “high criticality strategic programs,” requiring Cabinet-level approvals and multi-decade commitments. Private-sector leaders are urging the government to adopt a dual-track model: one centered on GTRE–Safran, and one on domestic private capabilities.

Expert View: A Multi-Track Engine Strategy

Defense analysts say bidding for an independent 110kN aero engine reflects a maturing of India’s aerospace ecosystem. According to propulsion experts, creating multiple development streams mitigates technological risk and builds domestic competition, which is standard practice in the US, France, and UK during major engine programs.

“India will need at least two to three viable domestic engine houses over the next decade if it wants to field next-generation fighters without foreign constraints,” said a former Indian Air Force engineering officer. He added that engine development cycles typically span 10–15 years, making early investment crucial.

What’s Next

If approved, the independent private-sector propulsion program could begin component-level testing by the late 2020s, with full engine demonstrators expected in the early 2030s. The push also aligns with India’s broader defense export ambitions, where indigenous engines are seen as essential for avoiding restrictive end-user licensing.

As India advances toward greater aerospace autonomy, the 110kN aero engine initiative—both public and private—remains central to the country’s vision of deploying fully indigenous fighter aircraft in the decades ahead.

Get real time update about this post category directly on your device, subscribe now.

6 comments

[…] that constructing a high-altitude airfield under extreme weather conditions was a “significant engineering challenge,” but essential to strengthening India’s defensive […]

[…] Mission Engineering and Integration Activity, intended to bring together government, industry, and labs early for […]

[…] scenarios. The exercise brought together tactical air defense operators, acquisition officials, and industry engineers for a holistic assessment of detection, discrimination, and defeat […]

[…] assembling the export variant Su-57E in India, potentially under a framework aligned with Make in India defense manufacturing goals. The proposal arrives amid delays in India’s indigenous Advanced Medium […]

[…] and processes before committing them to operational production programs. By annually demonstrating advanced technologies and process improvements aligned with industry demands, Northrop Grumman aims to rapidly mature new materials and manufacturing […]

[…] digital development strategies that emphasize smart government, data driven decision making, and advanced security technologies. The Israel Azerbaijan artificial intelligence MOU provides a bilateral channel to align elements […]