Table of Contents

Over the past decade, electronic warfare (EW) has undergone a dramatic transformation — morphing from a largely support‑oriented capability into a core pillar of modern military strategy. As global conflicts become more complex, with drones, precision‑guided munitions, networked command‑and‑control (C2), satellite communications, and hybrid tactics playing major roles, EW has proved itself a force multiplier. Whether jamming enemy drones, spoofing satellite navigation, or deploying directed‑energy weapons, combatants now rely heavily on controlling the electromagnetic (EM) spectrum as a path to battlefield dominance.

This deep‑dive explores key advances in EW since 2015, illustrated with real‑world examples — especially from ongoing conflicts — analyzes implications for global security, and forecasts likely future trends.

Early Shift: From Niche Tool to Tactical Essential (2015–2018)

Tactical Drone Jamming — The First Real Test

Around 2015–2016, as small commercial drones proliferated globally, militaries realized these inexpensive, agile platforms could upend traditional air-defense strategies. In response, field‑deployable radio-frequency (RF) jammers and early counter‑unmanned aerial system (C‑UAS) kits began to emerge. These jammers allowed frontline units to deny enemy drones critical navigation or control links, forcing them to crash or return home.

This capability proved especially valuable against loitering munitions or reconnaissance assets — denying adversaries real‑time targeting data without needing interceptors or kinetic fire. The result: small, cheap drones lost much of their battlefield value when faced with effective EW.

The Rise of Software‑Defined EW Systems

By 2017, EW equipment began shifting from hardware‑locked radios and jammers to software-defined architectures. The advantage: forces could rapidly reconfigure jamming profiles, frequencies, and waveforms — adapting on the fly to new drones or communication methods. The rigid, long‑upgrade cycles of hardware-based systems gave way to more agile, modular, and future‑ready solutions.

This shift significantly reduced the lag between threat emergence and countermeasure deployment. It also laid the groundwork for more complex EW–cyber integration and automation down the line.

GPS Spoofing & Navigation Denial Enters the Picture

By 2018, adversaries began using deceptive techniques — such as GPS spoofing — to disrupt navigation-dependent platforms. Spoofed GPS or GNSS signals could mislead drones, missiles, or vehicles into misnavigation, leading to aborted missions or dangerous misdrops.

This development exposed a critical vulnerability: as much of modern warfare had become satellite- and GPS-reliant (for navigation, targeting, communication), disrupting those signals could undercut high-tech capabilities without ever shooting a shot.

EW Steps Up: Satellite Communications, Cyber Integration, and AI (2019–2022)

EW Expands into Space: Targeting SATCOM & Satellite-Dependent Systems

By 2019, defense planners realized that EW doesn’t end on land or in the air — it extends into space. Satellite communications (SATCOM), linking command centers, ISR (intelligence‑surveillance‑reconnaissance) satellites, drones, and beyond, became prime EW targets. Jamming, spoofing, or disrupting SATCOM links could cripple an adversary’s high‑end C2 and ISR infrastructure.

In response, militaries began investing in anti‑jam waveforms, resilient satellite links, and multi-layered communication architecture — spanning terrestrial, air, and space domains. The space domain thus became a new battleground, part of broader multi-domain operations.

AI & Machine Learning Make EW Smarter

From 2020 onward, artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) began to transform EW operations. Automated signal classification, real-time spectrum analysis, and pattern recognition allowed EW systems to sift through RF clutter quickly, identify hostile emissions, and prioritize jamming or disruption tasks.

This shift significantly trimmed down response times. Instead of waiting for human analysts to identify signals and assess threats, AI-enabled systems could act almost instantly — vital in fast-moving conflicts. It also marked the convergence of EW with cyber and information warfare, blurring traditional domain boundaries.

Integrating EW and Cyber: A Single Operational Layer

Between 2021 and 2022, the boundaries between EW and cyber operations began to fade. Coordinated jamming, spoofing, and cyber intrusion became standard. For example, jamming enemy communications ahead of a cyber breach could mask the latter, or confuse defenders.

Simultaneously, with the growing use of battlefield drones — both in surveillance and strike roles — counter‑drone EW became a high priority. Forces adopted layered C‑UAS defenses: RF jamming, radar and sensor detection, optical targeting, and kinetic or directed‑energy takedown.

Together, EW + cyber + kinetic systems formed an integrated “multi‑domain interference architecture,” complicating defenses and forcing adversaries to adapt on several fronts simultaneously.

Real‑World Proof: EW in Contemporary Conflicts (2022–2025)

Nowhere has the transformation of EW been more evident than in the conflict in Ukraine — a testing ground for 21st‑century EM warfare. The fight has brought dramatic examples of both innovation and adaptation, as both sides race to control the electromagnetic environment.

Case Study: Jamming & Spoofing Russian UAVs

Since the full‑scale invasion in 2022, Russian forces have launched thousands of UAVs — reconnaissance drones, loitering munitions, and kamikaze drones alike. However, Ukrainian forces have turned to EW as a cornerstone of drone defense.

- According to defense‑open sources, in large drone strikes involving dozens to hundreds of drones, a significant portion have been lost due to EW interference rather than air defense systems.

- Ukrainian forces reportedly used signal‑hopping “walkie‑talkies,” portable jammers, and satellite‑spoofing “mesh networks” to interfere with UAV control and satellite navigation links.

- In some documented attacks, EW disruption caused entire salvos of drones or missiles to miss or divert off course.

These examples demonstrate the real-world impact: EW, rather than expensive kinetic interceptors, is often the first line of defense against drone swarms and long-range UAV strikes.

Directed Energy & HPM: Enter the Microwave Age

Beyond jamming and spoofing, forces are now experimenting with directed-energy weapons (DEWs) — particularly high‑power microwave (HPM) systems — to neutralize drone threats and disrupt electronics.

One prominent example is Leonidas HPM system, developed by Epirus in the United States. Leonidas can emit a microwave beam that disables electronics over a wide area — effective against drone swarms, sensors, and even small ground or sea vehicles.

Because it relies on electromagnetic disruption rather than kinetic destruction, such weapons minimize collateral damage and can neutralize GPS‑denied or autonomous drones (which reject traditional RF jamming). Their mobility — including trailer‑mounted versions or drone‑carried pods — improves flexibility and rapid deployment.

In Ukraine, there have been reports of laser- and directed‑energy systems being used to counter UAVs and missiles. While neither side has published full technical specifications, these deployments mark a significant shift: EW is no longer just “noise and deception,” but can physically destroy or disable enemy systems.

Targeting Enemy EW Assets — EW vs EW

As EW becomes more central, adversaries treat EW nodes themselves as high‑value targets. Ukrainian forces have reportedly located and destroyed several Russian EW vehicles and jamming sites — including mobile radar relays and communication jammers.

Destroying EW assets — by artillery, drones, or precision fire — denies an opponent spectrum control and undermines their ability to degrade friendly operations. This development underscores how modern warfare increasingly treats the EM spectrum as terrain: control matters as much as physical ground.

Technology Trends & Innovation: What’s Driving the EW Surge

Beyond frontline use, several technological and doctrinal developments have accelerated EW’s growth over the past decade.

Photonic & Chip‑Based EW: Miniaturization Meets Capability

Traditionally, EW systems were bulky, power-hungry, and required specialized platforms. Recent research, however, points to breakthrough advances in photonic chip‑based jamming systems. For example, a newly developed photonic chip-based reconfigurable radar jamming generator can produce complex jamming waveforms on a tiny 25 mm² silicon chip — generating multiple false‑target signals across 20 GHz bandwidth.

This kind of miniaturization opens the door for embedding EW capability into smaller platforms — drones, vehicles, even backpacks — dramatically expanding who can use EW and where. Instead of relying solely on vehicle-mounted jammers or fixed installations, insurgent groups or lightly equipped forces might soon have credible EW capabilities.

UAV‑Focused EW & Cyber‑EW Convergence

The growth of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) in recon, strike, and loitering roles has driven many EW innovations. A recent academic survey outlines the growing threat of cyber- and EW-based attacks on UAV avionics and comms systems — and equally growing defensive tools aimed at mitigating them.

Given that many UAVs now rely on digital links, GPS/GNSS navigation, and networked control, EW and cyber techniques increasingly overlap. Jamming, spoofing, signal‑injection, and cyber intrusion can all disrupt UAV operations; modern defense doctrine treats this as a unified “electromagnetic + cyber” domain.

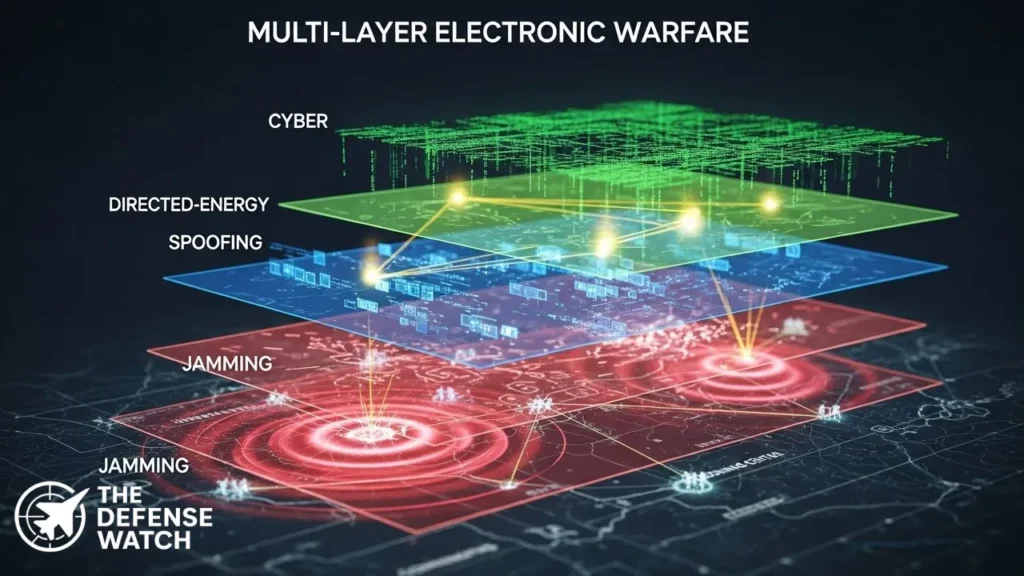

Multi‑Layer, Multi‑Domain Interference Models

A recent academic paper proposed an advanced “multi‑layer interference model” to counter AI‑driven cruise missiles: combining EW jamming, cyber attacks, and deception tactics to significantly degrade missile guidance accuracy. In simulation, this combined approach reduced missile target-acquisition success from over 90% to around 30%.

This proves the value — not just of single tools (like jamming) — but of integrated interference strategies across domains: EW, cyber, informational deception. As AI‑enabled weapons proliferate, such coordinated defense or interference strategies will likely become standard.

Strategic Implications: Why EW Matters Globally

The rise of EW isn’t just a tactical phenomenon — it carries broad strategic implications.

1. Democratization of Asymmetric Advantage

With chip-based EW, portable jammers, and UAV‑based systems, EW is no longer the exclusive domain of major powers. Smaller states — or even non-state actors — may field effective EW or counter‑UAV systems. This democratization reduces the advantage of traditional air or missile power, leveling the playing field in asymmetric conflicts.

2. Redefining Precision Warfare

Precision weapons — guided rockets, cruise missiles, GPS-guided bombs — have long been touted as the future of warfare. EW now challenges that paradigm: by spoofing or jamming guidance signals, or by deploying directed-energy weapons, adversaries can render costly precision munitions ineffective or unreliable.

This complicates procurement and operational planning. Militaries investing heavily in guided munitions must also invest in EW-resistant munitions, alternative guidance systems (inertial, optical), or robust counter‑EW measures.

3. Multi‑Domain Contest: Air, Space, Cyber, Electromagnetic

EW has transformed into a multi‑domain instrument. It intersects with cyber operations, space (satellite communications, GPS/GNSS), air (UAVs, missiles), maritime (ship radar, guidance), and ground forces. Commanders now must consider the electromagnetic environment as a dimension equal to terrain or airspace.

Deploying EW‑capable units, hardening friendly systems, and integrating EW into doctrine and training becomes critical. As such, national defense policy must increasingly treat EM spectrum dominance as a strategic resource.

4. The Pace of Innovation & the Challenge of Countermeasures

Because EW development cycles have shortened — thanks to software-defined radios, AI, photonic chips — adversaries must constantly adapt. A jamming method that works today may be bypassed tomorrow. This cat-and-mouse dynamic drives rapid innovation, but also carries risk: overreliance on EW may create new vulnerabilities (e.g. dependence on battery power, risk of counter-EW, or signal interception).

Regional Spotlight: EW in Non‑Western Militaries & New Markets

While a lot of reporting has focused on major powers like NATO, the U.S., Russia, or Ukraine, other regions are rapidly embracing EW — often with home‑grown systems tailored to local needs.

Take, for example, Spider-AD counter‑UAV system, developed by GIDS (Defense Science & Technology Organization, Pakistan). Unveiled at a 2024 defense exhibition, Spider‑AD can jam UAV communication and satellite navigation at ranges beyond 10 km, and comes in both vehicle‑mounted and man-portable tripod variants.

The existence of such systems shows that EW is no longer just for high-tech militaries — many developing states are investing in locally produced C‑UAS and EW systems to defend critical infrastructure, borders, and crowded urban areas against low-cost drone threats.

This trend likely will accelerate: as commercial drone and UAV technology becomes cheaper and more accessible, governments — especially those without full-spectrum air-defense — see EW and C‑UAS as cost‑effective solutions.

Future Forecast: What’s Next for EW?

Looking ahead to the next 5–10 years, several trends are likely to shape the evolution of electronic warfare.

Directed-Energy & HPM Weapons Proliferate

As power efficiency and miniaturization improve, directed-energy (DE) systems — including high-power microwaves, lasers, and EMP-based tools — will become more common. Expect mounting onto vehicles, drones, and even man-pack systems. These will likely be used for drone defense, counter‑sensor operations, or infrastructure denial — especially in urban or contested zones.

Photonic & Chip-Based EW Enables Distributed Spectrum Control

With the advent of photonic, chip-based jammers and signal generators, EW capability can be distributed widely: embedded into drones, small vehicles, or portable units. This will blur the line between “EW unit” and “frontline soldier” — making EM spectrum control more decentralized and harder to suppress.

AI + EW + Cyber → Fully Autonomous Interference Systems

Integrated systems that combine AI-driven signal detection, cyber intrusion, deception tactics, and directed‑energy response are likely. Such systems may operate semi-autonomously — detecting threats, choosing countermeasures, and executing them without human intervention. While ethical and control questions remain, the technology is emerging.

Anti‑EW Hardened Weapons and Redundant Navigation

As EW becomes more widespread, future weapons and systems will likely be built to resist EW: GPS‑independent navigation (inertial + optical), encrypted communication links, adaptive waveform radios, and redundant guidance systems. Similarly, more munitions may include fallback guidance or manual override.

EM Spectrum Governance & International Norms

With EW becoming ubiquitous and affecting civilian infrastructure (GPS, comms, satellites), international norms and regulations may emerge. Nations might negotiate “spectrum arms control,” or restrictions on jamming civilian frequencies. This is particularly likely if EW affects navigation, aviation, or humanitarian communications.

Why This Matters: EW’s Long‑Term Impact on Global Security

Electronic warfare represents a paradigm shift in how wars are fought — and who can fight them effectively. In the past, air superiority, heavy artillery, or advanced missiles determined battlefield dominance. In the 2020s and beyond, electromagnetic dominance may matter just as much.

For major powers, this means integrating EW into doctrine, investing in resilient communication and navigation, and preparing for multi-domain interference. For smaller states and non-state actors, EW and C‑UAS technologies provide cost-effective defensive tools — potentially reducing the threshold for localized conflicts or asymmetric warfare.

Ultimately, mastering EW will likely define the balance of power in many future conflicts — from drone‑heavy regional wars to high-tech strategic deterrence between great powers.

FAQs

Modern EW encompasses operations that control or deny the electromagnetic spectrum — including jamming communications, spoofing GPS signals, disrupting radar, interfering with satellite links, and even using directed‑energy weapons to disable electronics.

Kinetic warfare uses physical force — bullets, missiles, bombs. EW, in contrast, uses electromagnetic or cyber means. With EW, you can disable enemy systems — drones, missiles, communications — without physical destruction, often silently and with minimal risk of collateral damage.

Not exactly — but they increasingly overlap. EW deals with the electromagnetic spectrum (radio, radar, satellite), while cyber warfare targets networks, software, and digital infrastructure. Modern doctrine often treats them as a unified domain, because many systems (drones, missiles, comms) rely on both.

Yes. Advances in software-defined radios, photonic chips, portable jammers, and cheap drones mean that even smaller or less‑resourced actors can field credible EW or counter‑UAV systems. That lowers the barrier to entry for asymmetric or “hybrid” conflicts.

Probably the rise of autonomous EW systems — AI-driven tools that can detect, classify, and neutralize threats in real time — combined with directed-energy weapons. These could make the EM spectrum a critical battlefield in its own right.

Get real time update about this post category directly on your device, subscribe now.

5 comments

[…] is modular, built to support different mission profiles including air-to-air combat, strike, electronic warfare, and surveillance — depending on payload and […]

[…] F4.1 upgrade bundles not only the heavy-bomb capability but also improved sensors, connectivity, electronic warfare and anti-cyber protection […]

[…] the rise of drone swarms, fast attack craft, and missile threats in East Asia. By adopting directed-energy weapons, Japan strengthens its defensive posture while keeping pace with allied navies in terms of […]

[…] Systems & Technology Research LLC, based in Woburn, Massachusetts, will continue development work under contract HR001123C0095. Fiscal 2026 research and development funds totaling $9,645,267 are being obligated at the time of award, the Pentagon said. […]

[…] a specialized instrument designed to improve measurements of the Earth’s orientation for the GPS coordinate system. This technology enables more precise geodetic measurements and contributes to enhanced overall […]