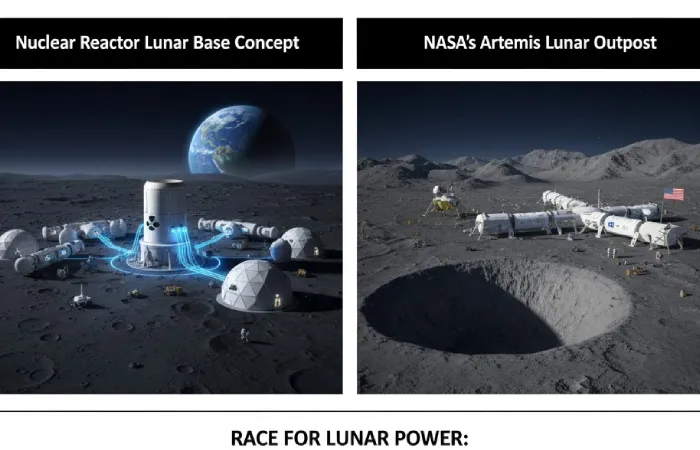

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) has accelerated its plans to deploy a nuclear-fission reactor on the surface of the Moon by 2030, setting a target power output of around 100 kilowatts and signaling a strategic move in the expanding lunar infrastructure race. Recent reports indicate that this timeline positions Washington ahead of the China National Space Administration (CNSA) and its Russian partners’ goal of building a lunar reactor by 2035.

Background

The push for nuclear power on the Moon comes amid renewed competition in space beyond traditional exploration. Solar and battery systems struggle with the lunar day-night cycle—approximately two weeks of sunlight followed by two weeks of darkness—making sustained operations difficult. A compact fission reactor could enable permanent bases, power-intensive activities and deep-space precursor missions, including those envisioned under the Artemis program.

Prior NASA initiatives such as the Kilopower experimental reactor project advanced designs for small reactors (1–10 kW) for space applications. These are now being scaled by NASA and industry toward 100 kW class systems for lunar surface deployment.

Meanwhile, China has indicated via a presentation that its broader lunar base initiative—the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS)—will include a nuclear power component, with a baseline manned base expected by 2035.

Details of the Plan

According to policy documents obtained by media outlets, NASA has instructed industry to submit proposals for a lunar surface reactor capable of producing about 100 kW of electrical power by 2030. The directive also notes that the first nation to deploy such a reactor might declare exclusive zones (“keep-out zones”) around its lunar installations, influencing future access.

In a related briefing, interim NASA administrator Sean Duffy emphasized: “To have a base on the Moon, we need energy.” He described the drive as part of a broader “second space race”.

Technical challenges remain significant. In the Moon’s vacuum environment, conventional cooling methods are inadequate. Engineers must design systems that manage heat rejection via radiators and possibly use conduction to the lunar regolith. NASA’s Fission Surface Power project addresses these vacuum-cooling and shielding issues.

China’s lunar reactor plan reportedly targets the same class of power but seeks to deploy by 2035. A Chinese space official, Pei Zhaoyu, presented slides showing a reactor component for the ILRS at a forum in Shanghai earlier in the year.

Expert and Policy Perspectives

From a defense-and-space policy standpoint, the lunar nuclear reactor initiative carries dual-use implications. Reliable power on the Moon could support infrastructure that, while civilian in nature, can bolster strategic presence. The possibility of “keep-out zones” raises questions about how lunar sovereignty and access rights will be managed under the Outer Space Treaty (1967).

Dr. Laura Kirkpatrick, a space-policy analyst, commented: “Deploying nuclear power enables not only habitats but also continuous operations—telemetry, robotics, mining—so whoever does it first gains a significant infrastructure head-start.”

On the technical side, the critical path lies in coupling compact fission units with reliable heat-rejection systems suitable for the lunar vacuum and dust environment. The burn-time, shielding mass, launch mass and automated deployment are all major hurdles. Previous terrestrial micro-reactors such as the Project Pele design for the U.S. Army reflect some of these challenges, though not in lunar conditions.

What’s Next

If NASA meets its 2030 target, the deployment of a 100 kW lunar reactor would mark a major milestone in the Artemis programme’s goal of establishing a sustainable lunar presence. It could also force competing actors, including China–Russia, to accelerate their own timelines or adjust base designs accordingly.

For industry, the next steps will include issuing requests for proposals, selecting commercial partners and commencing ground tests of reactor modules. NASA’s timeline calls for industry consultation within 60 days of the directive.

On the geopolitical front, lunar infrastructure power systems could become a new domain of strategic competition, with infrastructure-led influence extending beyond Earth orbit. The implementation of such systems may influence future agreements on lunar operations, commercial mining rights, and international collaboration.

2 comments

[…] light carrier program eyes 2033 entry, amplifying U.S. alliance […]

[…] engines, which means they need regular refueling and lack the almost unlimited reach that nuclear power provides. China is also building a future carrier design (Type 004) that may be nuclear and larger […]